Cities Were Shrinking but Now Growing Again

An abased firm in the Delray neighborhood of Detroit, Michigan

Shrinking cities or urban depopulation are dense cities that have experienced a notable population loss. Emigration (migration from a place) is a common reason for urban center shrinkage. Since the infrastructure of such cities was built to support a larger population, its maintenance can go a serious concern. A related phenomenon is counterurbanization.

Definition [edit]

Origins [edit]

The phenomenon of shrinking cities generally refers to a metropolitan area that experiences significant population loss in a brusque flow of time.[1] The process is likewise known every bit counterurbanization, metropolitan deconcentration, and metropolitan turnaround.[two] It was popularized in reference to Eastern Europe post-socialism, when old industrial regions came nether Western privatization and commercialism.[ane] [3] Shrinking cities in the United States, on the other mitt, have been forming since 2006 in dumbo urban centers while external suburban areas go on to grow.[4] Suburbanization in tandem with deindustrialization, human migration, and the 2008 Dandy Recession all contribute to origins of shrinking cities in the U.Southward.[one] Scholars estimate that i in 6 to one in four cities worldwide are shrinking in countries with expanding economies and those with deindustrialization.[1] All the same, there are some issues with the concept of shrinking cities, equally it seeks to group together areas that undergo depopulation for a variety of complex reasons. These may include an aging population, shifting industries, intentional shrinkage to improve quality of life, or a transitional phase, all of which crave different responses and plans.[5]

Causes [edit]

There are various theoretical explanations for the shrinking metropolis miracle. Hollander et al.[6] and Glazer[vii] cite railroads in port cities, the depreciation of national infrastructure (i.e., highways), and suburbanization as possible causes of de-urbanization. Pallagst[1] also suggests that shrinkage is a response to deindustrialization, every bit jobs move from the city core to cheaper land on the periphery. This instance has been observed in Detroit, where employment opportunities in the automobile industry were moved to the suburbs because of room for expansion and cheaper acreage.[8] Bontje[3] proposes 3 factors contributing to urban shrinkage, followed by 1 suggested by Hollander:

- Urban evolution model: Based on the Fordist model of industrialization, information technology suggests that urbanization is a cyclical process and that urban and regional decline volition eventually permit for increased growth[3]

- One company town/monostructure model: Cities that focus too much on one branch of economic growth brand themselves vulnerable to rapid declines, such equally the case with the automobile manufacture in Flint.[iii]

- Stupor therapy model: Especially in Eastern Europe post-socialism, state-endemic companies did non survive privatization, leading to plant closures and massive unemployment.[three]

- Smart decline: City planners have utilized this term and inadvertently encouraged decline by "planning for less—fewer people, fewer buildings, fewer country uses.".[6] It is a development method focused on improving the quality of life for current residents without taking those residents' needs into account, thus pushing more people out of the metropolis core.[half-dozen]

Furnishings [edit]

Economic [edit]

The shrinking of urban populations indicates a changing of economic and planning weather of a city. Cities begin to 'compress' from economic decline, usually resulting from war, debt, or lack of production and work forcefulness.[9] Population pass up affects a big number of communities, both communities that are far removed from and deep inside large urban centers.[nine] These communities usually consist of native people and long-term residents, so the initial population is not large. The outflow of people is then detrimental to the product potential and quality of life in these regions, and a refuse in employment and productivity ensues.[ix]

Social and infrastructural [edit]

Shrinking cities experience dramatic social changes due to fertility decline, changes in life expectancy, population crumbling, and household structure. Another reason for this shift is job-driven migration.[nine] This causes different household demands, posing a challenge to the urban housing market and the evolution of new land or urban planning. A refuse in population does not inspire conviction in a city, and frequently deteriorates municipal morale. Coupled with a weak economy, the city and its infrastructure begin to deteriorate from lack of upkeep from citizens.[ citation needed ]

Political [edit]

Historically, shrinking cities have been a taboo topic in politics. Representatives ignored the problem and refused to deal with it, leading many to believe it was non a real problem. Today, urban shrinkage is an best-selling outcome, with many urban planning firms working together to strategize how to combat the implications that affect all dimensions of daily life.[ix]

International perspectives [edit]

Old Socialist regions in Europe and Key Asia have historically suffered the most from population pass up and deindustrialization. Due east German cities, also as former Yugoslavian and Soviet territories, were significantly affected past their weak economical situation afterward the autumn of socialism. The reunification of European countries yielded both benefits and drawbacks. German cities similar Leipzig and Dresden, for example, experienced a drastic population decline equally many people emigrated to western cities like Berlin. Hamburg in particular experienced a population boom with tape production yields in 1991, afterwards the unification of Germany. Conversely, Leipzig and Dresden suffered from a declining economy and a neglected infrastructure. These cities were built to support a much larger population. Nevertheless, both Dresden and Leipzig are now growing once more, largely at the expense of smaller cities and rural areas. Shrinking cities in the United States face different issues, with much of the population migrating out of cities to other states for better economic opportunities and safer conditions. Advanced capitalist countries generally have a larger population, so this shift is not equally dangerous equally it is to post-socialist countries. The United States besides has more firms willing to rehabilitate shrinking cities and invest in revitalization efforts. For example, after the 1989 Loma Prieta convulsion in San Francisco in 1989, the dynamics between the city and its residents provoked alter and plans accomplished visible improvements in the city. Past contrast, cities in Frg have non gotten the same attention. Urban planning projects take a long time to exist approved and established. As of now, Leipzig is taking steps toward making the city more than nature-oriented and 'green' so that the population can be beginning stabilized, and then the country can focus on cartoon the population back into the city.[10]

Theories [edit]

The appreciable demographic out-migration and disinvestment of upper-case letter from many industrial cities across the globe following World War Ii prompted an academic investigation into the causes of shrinking cities, or urban decline. Serious issues of justice, racism, economic and health disparity, also as inequitable power relations, are consequences of the shrinking cities phenomenon. The question is, what causes urban decline and why? While theories do vary, three primary categories of influence are widely attributed to urban turn down: deindustrialization, globalization, and suburbanization.

Deindustrialization [edit]

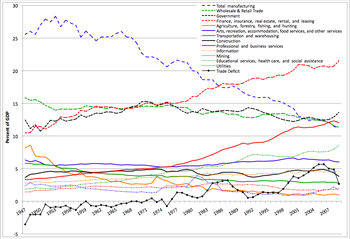

Sectors of the United states of america Economy equally pct of Gross domestic product 1947–2009.[xi]

One theory of shrinking cities is deindustrialization or, the process of disinvestment from industrial urban centers.[12] This theory of shrinking cities is mainly focused on post-World War II Europe equally manufacturing declined in Western Europe and increased in the U.s., causing a shift of global economic power to the United States.[13] The result was that Western European industrialization largely ceased, and culling industries arose.[xiii] This economic shift is clearly seen through the U.k.'s rise of a service sector economy.[14] With the decline in industry, many jobs were lost or outsourced, resulting in urban turn down and massive demographic motion from former industrial urban centers into suburban and rural locales.[14]

Postal service-World War II politics [edit]

Rapid privatization incentives encouraged under the United States-sponsored post-World State of war 2 economic assist policies such as the Marshall Plan and Lend-Charter plan, motivated costless-market, capitalist approaches to governance across the Western European economic landscape.[12] The result of these privatization schemes was a movement of majuscule into American manufacturing and financial markets and out of Western European industrial centers.[fourteen] American loans were besides used as political currency contingent upon global investment schemes meant to stifle economical development within the Soviet-centrolineal Eastern Bloc.[15] With extensive debt tying capitalist Europe to the Us and financial blockades inhibiting full development of the communist Eastern one-half, this Cold War economic ability structure greatly contributed to European urban decline.

The case of Cracking United kingdom [edit]

19th century Groovy Uk became the outset global economic superpower, because of superior manufacturing technology and improved global communications such equally steamships and railways.

Great Britain, widely considered the offset nation to fully industrialize, is oft used as a example study in support of the theory of deindustrialization and urban decline.[14] Political economists oft point to the Cold State of war era as the moment when a awe-inspiring shift in global economic power structures occurred.[14] The former "Great Empire" of the Uk was built from industry, merchandise and financial dominion. This control was, however, effectively lost to the United states nether such programs as the Lend-Charter and Marshall Programme.[xiv] As the global fiscal market moved from London to New York City, and so too did the influence of capital letter and investment.

With the initial decades following Globe War II dedicated to rebuilding or, readjusting the economic, political and cultural role of United kingdom within the new world order, it wasn't until the 1960s and 1970s that major concerns over urban reject emerged.[14] With industry moving out of Western Europe and into the United States, rapid depopulation of cities and movement into rural areas occurred in Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland.[14] Deindustrialization was advanced further under the Thatcherite privatization policies of the 1980s.[xiv] Privatization of manufacture took abroad all remaining land protection of manufacturing. With industry now under private ownership, "gratis-market place" incentives (forth with a strong pound resulting from North Sea Oil) pushed farther move of manufacturing out of the United Kingdom.[14]

Under Prime Minister Tony Blair, the Great britain finer tried to revamp depopulated and unemployed cities through the enlargement of service sector industry.[fourteen] This shift from manufacturing to services did non, however, reverse the trend of urban decline observed beginning in 1966, with the exception of London.[fourteen]

The case of Leipzig [edit]

Leipzig after bombing in World War II

Leipzig serves every bit an example of urban decline on the Eastern half of post-World War Ii Europe. Leipzig, an Due east German language city under Soviet domain during the Cold War era, did not receive acceptable authorities investment every bit well as market place outlets for its industrial goods.[13] With the stagnation of demand for production, Leipzig began to deindustrialize every bit the investment in manufacturing stifled.[16] This deindustrialization, demographers theorize, prompted populations to drift from the metropolis center and into the country and growing suburbs in lodge to find work elsewhere.[thirteen] Since the 2000s, Leipzig has re-industrialized and is once again a growing urban realm.

The case of Detroit [edit]

Although most major research on deindustrialization focuses on post-World War Two Europe, many theorists also turn to the case of Detroit, Michigan as further evidence of the correlation betwixt deindustrialization and shrinking cities.[17] Detroit, nicknamed Motor City because of its expansive automobile manufacturing sector, reached its population peak during the 1950s.[18] As European and Japanese industry recovered from the destruction of World State of war II, the American motorcar industry no longer had a monopoly advantage. With new global market competition, Detroit began to lose its unrivaled position every bit "Motor City".[18] With this falling demand, investment shifted to other locations exterior of Detroit. Deindustrialization followed as production rates began to drop.

Globalization [edit]

As axiomatic from the theory of deindustrialization, political economists and demographers both place huge importance on the global flows of capital and investment in relation to population stability.[19] Many theorists indicate to the Bretton Woods Conference as setting the stage for a new globalized age of merchandise and investment.[xix] With the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank in add-on to the United States' economical aid programs (i.eastward., Marshall Programme and Lend-Charter), many academics highlight Bretton Forest as a turning point in world economic relations. Under a new academic stratification of adult and developing nations, trends in capital letter investment flows and urban population densities were theorized following mail service-World War II global fiscal reorganization.[twenty]

Product life-cycle theory [edit]

The product life-wheel theory was originally developed by Raymond Vernon to help improve the theoretical understanding of modern patterns of international trade.[nineteen] In a widely cited report by Jurgen Friedrichs, "A Theory of Urban Decline: Economy, Census and Political Elites," Friedrichs aims to analyze and build upon the existing theory of product life-cycle in relation to urban refuse.[15] Accepting the premise of shrinking cities as upshot of economic decline and urban out-migration, Friedrichs discusses how and why this initial economical decline occurs.[xv] Through a dissection of the theory of product life-cycle and its suggestion of urban decline from disinvestment of outdated industry, Friedrichs attributes the root cause of shrinking cities as the lack of industrial diversification inside specific urban areas.[15] This lack of diversification, Friedrichs suggests, magnifies the political and economical power of the few major companies and weakens the workers' power to insulate against disinvestment and subsequent deindustrialization of cities.[xv] Friedrichs suggests that lack of urban economic diversity prevents a thriving industrial heart and disempowers workers.[15] This, in turn, allows a few economic elites in old-industrial cities such as St. Louis, Missouri and Detroit in the United States, to reinvest in cheaper and less-regulated third globe manufacturing sites.[21] The event of this economic decline in one-time-industrial cities is the subsequent out-migration of unemployed populations.

Neoliberal critique [edit]

Contempo studies have further built upon the product life-cycle theory of shrinking cities. Many of these studies, however, focus specifically on the effects of globalization on urban decline through a critique of neoliberalism. This contextualization is used to highlight globalization and the internationalization of production processes as a major driver causing both shrinking cities and subversive development policies.[22] Many of these articles depict upon instance studies looking at the economical relationship between the United States and China to analyze and support the master argument presented. The neoliberal critique of globalization argues that a major commuter of shrinking cities in adult countries is through the outflow of capital into developing countries.[xx] This outflow, according to theorists, is caused past an disability for cities in richer nations to detect a productive niche in the increasingly international economic organization.[20] In terms of disinvestment and manufacturer movement, the ascension of China's manufacturing industry from United States outsourcing of inexpensive labor is often cited as the most applicable current example of the product life-cycle theory.[20] Dependency theory has likewise been practical to this analysis, arguing that cities outside of global centers experience outflow as inter-urban competition occurs.[23] Based on this theory, information technology is argued that with the exception of a few core cities, all cities eventually shrink as capital flows outward.

Suburbanization [edit]

The migration of wealthier individuals and families from industrial city centers into surrounding suburban areas is an observable tendency seen primarily within the United states during the mid to belatedly 20th century.[24] Specific theories for this flying vary across disciplines. The two prevalent cultural phenomenons of white flight and motorcar culture are, nonetheless, consensus trends beyond academic disciplines.[25]

White flying [edit]

White flight mostly refers to the movement of large percentages of Caucasian Americans out of racially mixed Usa city centers and into largely homogenous suburban areas during the 20th century.[18] The upshot of this migration, according to theorists studying shrinking cities, was the loss of money and infrastructure from urban centers.[18] As the wealthier and more than politically powerful populations fled from cities, so too did funding and government involvement. The event, according to many academics, was the key decline of urban wellness beyond United states cities starting time in the 20th century.[xviii]

The product of white flight was a stratification of wealth with the poorest (and more often than not minority) groups in the center of cities and the richest (and mostly white) outside the city in suburban locations.[17] Every bit suburbanization began to increase through to the late 20th century, urban health and infrastructure precipitously dropped. In other words, United States urban areas began to turn down.[17]

Mid-20th-century political policies profoundly contributed to urban disinvestment and turn down. Both the product and intent of these policies were highly racial oriented.[17] Although discrimination and racial segregation already existed prior to the passage of the National Housing Act in 1934, the structural process of discrimination was federally established with the Federal Housing Administration (FHA).[18] The issue of the establishment of the FHA was redlining. Redlining refers to the demarcation of certain districts of poor, minority urban populations where government and private investment were discouraged.[17] The decline of minority inner urban center neighborhoods was worsened under the FHA and its policies.[17] Redlined districts could not improve or maintain a thriving population under conditions of withheld mortgage capital.[17]

Car culture and urban sprawl [edit]

In combination with the racial drivers of white flight, the development of a uniquely American car culture besides led to further development of suburbanization and after, urban sprawl.[27] Equally car culture made driving "cool" and a key cultural aspect of "American-ness," suburban locations proliferated in the imaginations of Americans as the ideal landscape to live during the 20th century.[27] Urban decline, under these conditions, only worsened.[27]

The more recent phenomenon of urban sprawl beyond American cities such every bit Phoenix and Los Angeles, were only made possible under the weather condition of a car civilisation.[27] The impact of this machine culture and resulting urban sprawl is, according to academics, threefold. Kickoff, although urban sprawl in both shrinking and growing cities have many similar characteristics, sprawl in relation to declining cities may be more rapid with an increasing desire to motility out of the poor, inner-city locations.[thirteen] 2d, there are many similarities in the characteristics and features of suburban areas around growing and declining cities.[thirteen] Third, urban sprawl in failing cities can be contained by improving land apply within inner city areas such as implementing micro-parks and implementing urban renewal projects.[xiii] In that location are many similarities betwixt urban sprawl in relation to both failing and growing cities. This, therefore, provides similar intervention strategies for controlling sprawl from a urban center planning signal of view.

Interventions [edit]

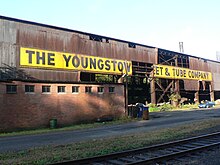

Dissimilar interventions are adopted past different city governments to deal with the problem of city shrinkage based on their context and development. Governments of shrinking cities such as Detroit and Youngstown take used new approaches of adapting to populations well below their peak, rather than seeking economic incentives to boost populations to previous levels before shrinkage and embracing growth models.

Green retirement city [edit]

Research from Europe proposes "retirement migration" as one strategy to deal with city shrinkage. The idea is that abandoned properties or vacant lots can be converted into light-green spaces for retiring seniors migrating from other places. As older individuals migrate into cities they can bring their knowledge and savings to the city for revitalization.[28] Retiring seniors are oft ignored by the communities if they are not actively participating in community activities. The greenish retirement city approach could besides have benefits on social inclusion of seniors, such every bit urban gardening.[28] The approach could also act equally a "catalyst in urban renewal for shrinking cities".[28] Accommodations, in the meanwhile, have to exist provided including accessibility to customs facilities and wellness intendance.

Establishing a green retirement city would exist a good approach to avert tragedies like the 1995 Chicago oestrus wave. During the oestrus wave, hundreds of deaths occurred in the metropolis, particularly in the inner neighborhood of the city. Victims were predominantly poor, elderly, African American populations living in the heart of the city.[29] Afterwards inquiry pointed out that these victims were socially isolated and had a lack of contact with friends and families.[29] People who were already very sick in these isolated, inner neighborhoods were also affected and might have died sooner than otherwise.[29] The high crime rate in the inner decomposable metropolis also accounted for the high rate of deaths as they were afraid to open their windows. Therefore, a green retirement city with sufficient customs facilities and support would accommodate needs for elderly population isolated in the poor, inner city communities.

Right-sizing [edit]

The thought of "right-sizing" is defined every bit "stabilizing dysfunctional markets and distressed neighborhoods by more closely aligning a city's congenital environment with the needs of existing and foreseeable time to come populations by adjusting the corporeality of land bachelor for evolution."[30] Rather than revitalize the entire urban center, residents are relocated into full-bodied or denser neighborhoods. Such reorganization encourages residents and businesses in more sparsely populated areas to move into more densely populated areas.[31] Public amenities are emphasized for improvement in these denser neighborhoods. Abased buildings in these less populated areas are demolished and vacant lots are reserved for future greenish infrastructure.[30]

The city of Detroit has adopted right-sizing approaches in its "Detroit Work Project" plan. Many neighborhoods are simply x–xv% occupied,[32] and the program encourages people to concentrate in nine of the densest neighborhoods.[32] Under the program, the city performs several tasks including: prioritizing public safety, providing reliable transportation and demolition plans for vacant structures.[33]

Although the "right-sizing" approach may seem bonny to bargain with vast vacant lots and abandoned houses with isolated residents, it can exist problematic for people who are incapable of moving into these denser neighborhoods.[31] In the case of Detroit, although residents in decaying neighborhoods are not forced to motion into concentrated areas, if they live outside designated neighborhoods they may not get public services they crave.[31] This is because communities in shrinking cities often are low-income communities where they are racially segregated.[34] Such segregation and exclusion may "contribute to psychosocial stress level" as well and further add burden to the quality of living environments in these communities.[34]

Smart shrinkage [edit]

The idea of "smart shrinkage", in some regards, is similar to dominant growth-based models that offer incentives encouraging investment to spur economic and population growth, and reverse shrinkage. Nonetheless, rather than believing the city can return to previous population levels, the governments embrace shrinkage and accept having a significantly smaller population.[35] With this model, governments emphasize diversifying their economy and prioritizing funds over relocating people and neighborhoods.

Youngstown 2010 is an example of such an arroyo for the city of Youngstown, Ohio. The plan seeks to diversify the city'due south economic system, "which used to be almost entirely based on manufacturing".[36] Taxation incentive programs like Youngstown Initiative have as well "assisted in bringing in and retaining investment throughout the city."[37] Since the plan was introduced, many major investments accept been fabricated in the city. The downtown Youngstown has been besides transformed from a high offense rate surface area into a vibrant destination.[36]

Nevertheless, there are concerns that the smart shrinkage approach may worsen existing isolation of residents who cannot relocate to more vibrant neighborhoods. Environmental justice issues may surface from this approach if city governments ignore the types of industries planning investment and neighborhoods that are segregated.

Country bank [edit]

Land banks are often quasi-governmental counties or municipal regime that manage the inventory of surplus vacant lands. They "let local jurisdictions to sell, demolish and rehabilitate large numbers of abandoned and tax-runaway properties."[38] Sometimes, the state works directly with local governments to allow abandoned properties to have easier and faster resale and to discourage speculative buying.[38]

One of the almost famous examples of land banks is the Genesee County State Bank in the city of Flint, Michigan. As an industrial city with General Motors as the largest producer, declining auto sales with the availability of inexpensive labor in other cities led to reduction in the labor force of the metropolis. The main reason of the property or country abandonment problem in Flint was the state'southward revenue enhancement foreclosure system.[39] Abandoned properties were either transferred to individual speculators or became state-owned belongings through foreclosure, which encouraged low-end reuse of taxation-reverted country due to the length of fourth dimension between abandonment and reuse.[39]

The Land Banking company provides a series of programs to revitalize shrinking cities. In the case of Flint, Brownfield Redevelopment for previous polluted lands is controlled by the land bank to allow financing of demolition, redevelopment projects and make clean up through tax increment financing.[39] A "Greening" strategy is also promoted by using abandonment as an opportunity for isolated communities to engage in maintenance and improvement of vacant lots.[39] In the city, there is significant reduction in abandoned properties. Vacant lots are maintained by the banks or sold to adjacent land owners as well.[38]

Establishment of country banks could increment land values and tax revenues for farther innovation of the shrinking cities. Even so, The process of acquiring foreclosures tin exist troublesome as "information technology may require interest on the role of several jurisdictions to obtain clear title," which is necessary for redevelopment.[40] Economic problems that local residents take, including income disparities between local residents, cannot be solved by the country bank, with the addition of increasing rents and land values led by the revitalization of vacant land. Local leaders as well lack the potency to interrupt works that Land Banks do.[39] Environmental justice problems that are from previous polluting manufacture may not be fully addressed through shrinking city intervention and without opinions from local people. Therefore, a new approach of dealing with these vacant lots will be to work with non-profit local community groups to construct more than green open spaces among the declining neighborhoods to reduce vacant lots and create strong community commitments.[38]

Other approaches [edit]

Cities have used several other interventions to deal with city shrinkage. I such is the serial of policies adopted in the city of Leipzig in East Germany. They include construction of town houses in urban areas and Wächterhäuser, 'guardian houses' with temporary rental-free leases. Temporary employ of private belongings equally public spaces is also encouraged.[42] Altena, about Dortmund, has addressed the issue through partnership with civil society and the integration of immigrants.[43] [44] Another intervention is the revitalization of vacant lots or abandoned properties for artistic development and artists interactions such equally the Village of Arts and Humanities in N Philadelphia, where vacant lots and empty buildings are renovated with mosaics, gardens and murals.

Environmental justice [edit]

A speedily contracting population is oft viewed holistically, as a citywide and sometimes even regional struggle. However, shrinking cities, by their nature and how local officials reply to the phenomena, tin have a disproportionate social and environmental bear on on the less fortunate, resulting in the emergence of issues relating to environmental injustices. This paradigm was established well-nigh immediately afterward cities started shrinking in significance during the mid-20th century and persists today in varying forms.

Historical precedent [edit]

Although the concept of environmental justice and the movement information technology sparked was formally introduced and popularized starting in the late 1980s, its historical precedent in the context of shrinking cities is rooted in mid-20th century trends that took place in the United States.

In an American context, historical suburbanization and subsequent ill-fated urban renewal efforts are largely why the very poor and people of color are concentrated in otherwise emptied cities, where they are adversely plagued by weather condition which are today identified equally environmental injustices or environmental racism.[45] These conditions, although created and exacerbated through mid-20th century actions, still persist today in many cases and include: living in shut proximity to freeways; living without convenient access, if any, to healthy foods[46] and green infinite. Unlike white people, people of color were socially and legally barred from taking advantage of federal authorities policy encouraging suburban flight. For example, the early on construction of freeways[47] coupled with practices such as redlining and racially restrictive covenants, physically prevented people of color from participating in the mass migration to the suburbs, leaving them in – what would become – hollowed and fated city cores.[48] Considering income and race are deeply embedded in understanding the formation of suburbs and shrinking cities, whatsoever interventions responding to the shrinking city miracle will almost invariably confront issues of social and environmental justice. It is not the case in Europe, where suburbanization has been less extreme,[49] and drivers of shrinking cities are also more than closely linked to aging demographics, and deindustrialization.[50]

Case studies [edit]

In addition to discriminatory policy-driven decisions of the by, which acquired cities to contract in population and created inhospitable living conditions for the poor and people of color in urban cores, ecology justices concerns too ascend in present initiatives that seek solutions for cities struggling with considerable population losses.

New Orleans [edit]

New Orleans, like many major American cities, saw its population decrease considerably over the latter half of the 20th century, losing almost 50% of the population from its peak in 1960. In large part because of white flight and suburbanization, the population loss perpetuated existing racial segregation and left people of color (mostly African Americans) in the city center.[51] By 2000, vacant and abandoned backdrop made upwardly 12% of the housing stock.[52] The city was struggling economically[51] and in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, 134,344 of 188,251 occupied housing units sustained reportable damage, and 105,155 of them were severely damaged.[53] Considering of historical settlement patterns formed by racial restrictions in the first half of the 20th century,[51] African Americans were disproportionately impacted by the destruction.[54]

The corner of Wilton & Warrington streets, March, 2007, well-nigh two years after Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans

Responding to Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans Mayor C. Ray Nagin formed the Bring New Orleans Back Committee in September 2005.[55] The goal of the commission was to assist in redevelopment decision-making for the city. The committee shared its proposal for redevelopment in Jan 2006, however it faced some criticism related to environmental justice concerns. The commission's proposal was presented prior to many residents having returned to the city and their homes.[55] The process was not very inclusive, specially with locals of impacted areas, who were predominantly from disadvantaged communities. While the proposal addressed future potential flooding by incorporating new parks in depression-laying areas to manage storm water, the locations of the proposed greenspaces required the elimination of some of the low-income neighborhoods.[55] Residents largely viewed the proposal as forced displacement and every bit benefitting primarily more than affluent residents.[56] The proposal was roundly rejected past residents and advocates for residents.[54]

A afterwards intervention to convalesce the mounting abandonment and bane (which existed prior to Katrina just was exacerbated past the disaster) was Ordinance No. 22605, enacted by the New Orleans urban center council in 2007.[57] The rationale for the ordinance was to let the city to establish a "Lot Adjacent Door" program, which seeks to "help in the elimination of abandoned or blighted properties; to spur neighborhood reinvestment, heighten stability in the rental housing market, and maintain and build wealth within neighborhoods." The plan intended to give owner occupants the opportunity to buy abutting properties (city acquired backdrop formerly state-endemic or owned by the New Orleans Redevelopment Authorization) as a means of returning properties to neighborhood residents.[54] It afterward expanded to let whatever individual to purchase a property if that person or a family fellow member would live there. The bear upon of the program, yet, was unevenly distributed throughout the urban center. Although blackness neighborhoods in the low-laying topographical regions were striking the hardest by Katrina, affluent neighborhoods with loftier rates of owner occupancy meliorate absorbed vacant and abandoned properties than areas with more than rental units.[54]

Detroit [edit]

Perchance the city most commonly associated with the concept of shrinking cities, Detroit too has grappled with issues of environmental justice. Detroit'south electric current circumstances, equally information technology struggles to deal with a population less than half of that from its peak in 1950, are partially the directly effect of the same racist process, which left but the poor and people of colour in urban city centers.[58] The city presently faces economic strain since only vi percentage of the taxable value of real manor in the tri-county Detroit surface area is in the urban center of Detroit itself while the remaining 90-four percent is in the suburbs.[59] In recent years, the urban center has made attempts, out of necessity, to accost both its economic and population decline.

Gaps between Detroit'south remaining neighborhoods and homes form equally abased houses accept been demolished.

In 2010, Detroit mayor David Bing introduced a plan to demolish approximately 10,000 of an estimated 33,000 vacant homes[60] in the city considering they were "vacant, open, and dangerous".[61] The decision was driven by the reality that for fiscal constraints, the city'southward existing resource simply could not maintain providing services to all areas.[62] However, the decision likewise reflected a desire to "right-size" Detroit by relocating residents from dilapidated neighborhoods to "good for you" ones.[63] The idea of right-sizing and repurposing Detroit, however, is a contentious event.[64] Some locals are determined to stay put in their homes[62] while others compare the efforts to past segregation and forced relocation.[64] Mayor Bing clarified that people would not exist forced to motion, simply residents in sure parts of the metropolis "need to understand they're not going to get the kind of services they require."[65]

In add-on to right-sizing Detroit as a means to deal with a massively decreased metropolis population and economic shortfall, Mayor Bing too undertook budget cuts.[65] Although oft necessary and painful, sure cuts, such as those to the city's motorbus services[66] can produce harms in an environmental justice framework. In Detroit, despite the city's massive size and sprawl, roughly 26% of households have no automobile access, compared to 9.2% nationally.[67] From an ecology justice perspective this is significant considering a lack of automobile access, coupled with poor transit and historic decentralization, perpetuates what is often referred to as a spatial mismatch. While wealth and jobs are on the outskirts of the metropolitan region, disadvantaged communities are full-bodied in the inner-metropolis, physically far from employment without a ways of getting there.[68] Indeed, near 62% of workers are employed outside the city limit, and many depend on public transit.[67] Some debate that for Detroit this situation should more specifically be termed a "modal mismatch" because the poor of the inner-city are disadvantaged because they lack automobile access in a region designed for automobiles.[69]

Regardless of name, the situation is footling dissimilar and nonetheless embedded in historic racial and environmental injustices; the poor are clustered in an inner-city from past policies, which were often racially discriminatory, and cuts to public transportation reduce chore accessibility for the many households in Detroit that lack automobile access.

See also [edit]

- Climate justice

- Deurbanization

- Environmental justice

- Environmental racism

- Urban sprawl

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d due east Pallagst, One thousand. (2009). "Shrinking cities in the The states of America: 3 cases, three planning stories". The Futurity of Shrinking Cities. 1: 81–88.

- ^ Frey, William (1987). "Migration and Depopulation of the Metropolis: Regional Restructuring or Rural Renaissance". American Sociological Review. 52 (2): 240–287. doi:ten.2307/2095452. JSTOR 2095452.

- ^ a b c d e Bontje, M. (2005). "Facing the challenge of shrinking cities in Due east Federal republic of germany: The instance of Leipzig". GeoJournal. 61 (1): 13–21. doi:x.1007/sgejo-004-0843-7.

- ^ Hollander, J.; J. Németh (2011). "The premises of smart reject: a foundational theory for planning shrinking cities". Housing and Policy Debate. 21 (3): 349–367. doi:10.1080/10511482.2011.585164. S2CID 153694059.

- ^ Maheshwari, Tanvi. "Redefining Shrinking Cities. The Urban Fringe, Berkeley Planning Periodical".

- ^ a b c Hollander, J. (2010). "Moving Toward a Shrinking Cities Metric: Analyzing Land Use Changes Associated with Depopulation in Flint, Michigan". Cityscape. 12 (i): 133–152.

- ^ Glazer, Sidney (1965). Detroit: A Report in Urban Development. New York: Bookman Associates, Inc.

- ^ Martelle, Scott (2012). Detroit: A Biography. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press.

- ^ a b c d east Schteke, Sophie; Dagmar Haase (September 2007). "Multi-Criteria Assessment of Socio-Environmental Aspects in Shrinking Cities. Experiences from Eastern Germany". Ecology Affect Assessment Review. 28: 485.

- ^ Harms, Hans. "Changes on the Waterfront-Transforming Harbor Areas" (PDF).

- ^ "Who Makes It?". Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ a b Clark, David. Urban Decline (Routledge Revivals). Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f yard Couch, Chris, Jay Karecha, Henning Nuissl, and Dieter Rink. "Decline and sprawl: an evolving type of urban development – observed in Liverpool and Leipzig." European Planning Studies 13.1 (2007): 117-136.

- ^ a b c d e f grand h i j yard l Lang, Thilo. "Insights in the British Fence about Urban Decline and Urban Regeneration." Leibniz-Establish for Regional Development and Structural Planning (2005): one-25.

- ^ a b c d due east f Friedrichs, Jurgen (1993). "A Theory of Urban Pass up: Economy, Census and Political Elites". Urban Studies. 30 (6): 907–917. doi:x.1080/00420989320080851. S2CID 153359435.

- ^ Rall, Emily Lorance; Haase, Dagmar (2011). "Artistic intervention in a dynamic city: A sustainability assessment of an interim utilise strategy for brownfields in Leipzig, Germany". Mural and Urban Planning. 100 (3): 189–201. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.12.004.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g Sugrue, Thomas (2005). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Printing.

- ^ a b c d e f Rappaport, Jordan. "U.Southward. Urban Turn down and Growth, 1950 to 2000". Economic Review. 2003: 15–44.

- ^ a b c Vernon, Raymond (1979). "The Product Cycle Hypothesis In A New International Environment". Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 41 (4): 255–267. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.1979.mp41004002.x.

- ^ a b c d Martinez-Fernandez, Cristina; Audirac, Ivonne; Fol, Sylvie; Cunningham-Sabot, Emmanuèle (2012). "Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization". International Journal of Urban and Regional Enquiry. 36 (two): 213–225. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01092.x. PMID 22518881.

- ^ Rieniets, Tim (2009). "Shrinking Cities: Causes and Effects of Urban Population Losses in the Twentieth Century". Nature and Civilisation. iv (three): 231–254. doi:10.3167/nc.2009.040302.

- ^ Taylor, Yard. "The production-bicycle model: a critique." Environment and Planning xviii.six (1986): 751-761.

- ^ Silverman, R.M. "Rethinking shrinking cities: Peripheral dual cities have arrived." Journal of Urban Diplomacy (2018).

- ^ Voith, Richard. "City and suburban growth: substitutes or complements?" Business Review (1992): 21-33.

- ^ Mitchell, Clare J.A. (2004). "Making sense of counterurbanization". Journal of Rural Studies. xx (1): 15–34. doi:ten.1016/s0743-0167(03)00031-7.

- ^ The HOLC maps are part of the records of the FHLBB (RG195) at the National Archives 2 Archived 2016-x-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d Fulton, William B. Who sprawls most? How growth patterns differ across the U.S.. Washington, DC: Brookings Establishment, Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, 2001.

- ^ a b c Nefs, Yard; Alves, S; Zasada, I; Haase, D (2013). "Shrinking cities equally retirement cities? Opportunities for shrinking cities as green living environments for older individuals". Environment and Planning A. 45 (six): 1455–1473. doi:ten.1068/a45302. S2CID 154723141.

- ^ a b c Roper, R. E. (2003). ""Volume Review of "Rut Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago". Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. i (1): 7. doi:10.2202/1547-7355.1008. S2CID 109342150.

- ^ a b Schilling, Joseph; Logan, Jonathan (2008). "Greening the rust belt: A dark-green infrastructure model for correct sizing America'southward shrinking cities". Journal of the American Planning Association. 74 (4): 451–466. doi:ten.1080/01944360802354956. S2CID 154405955.

- ^ a b c Lauren, Davis (May 26, 2012). "Detroit plans to shrink past leaving half the metropolis in the dark". Gizmodo.

- ^ a b Chris, McGreal (December 17, 2010). "Detroit mayor plans to shrink city past cutting services to some areas". The Guardian.

- ^ "Transforming Detroit Handbook" City of Detroit. Web. v March 2014

- ^ a b Morello-Frosch, Rachel; Zuk, Miriam; Jerrett, Michael; Shamasunder, Bhavna; Kyle, Amy D. (2011). "Understanding the Cumulative Impacts of Inequality in Environmental Wellness: Implications for Policy". Health Affairs. xxx (5): 879–887. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0153. PMID 21555471.

- ^ Rhodes, James; Russo, John (2013). "Shrinking 'Smart'?: Urban Redevelopment and Shrinkage in Youngstown, Ohio". Urban Geography. 34 (3): 305–326. doi:10.1080/02723638.2013.778672. S2CID 145171008.

- ^ a b Lawson, Ethan. "Youngstown: A Shrinking City with Big Ideas" CEOs for Cities. July 25, 2013

- ^ Parris, Terry (2010-05-04). "Youngstown 2010: What shrinkage looks like, what Detroit could larn". Youngstown, Ohio: Model D.

- ^ a b c d Fredenburg, Julia. Land Banks to Revive Shrinking Cities: Genesee Canton, Michigan, Housing Policy & Equitable Development, PUAF U8237, May 10, 2011. Web. iv March 2014

- ^ a b c d eastward Gillotti, Teresa and Kildee, Daniel. "State Banks as Revitalization Tools: The Example of Genesee County and the City of Flintstone, Michigan."

- ^ Sage Computing, Inc (Baronial 2009). "Revitalizing Foreclosed Properties with Land Banks". HUD USER. Reston, VA.

- ^ http://world wide web.haushalten.org/de/english_summary.asp[ bare URL ]

- ^ URBACT. Finding opportunities in declining cities. Working with civil guild to reverse decline in small and medium sized towns, Saint-Denis, 2022 [i]

- ^ Schlappa, H. and Neill, J.V., From crisis to choice: re-imagining the time to come in shrinking cities, URBACT, Saint-Denis, 2013 https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/import/general_library/19765_Urbact_WS1_SHRINKING_low_FINAL.pdf

- ^ Robert Beuregard (2010). Malo André Hutson (ed.). Urban Communities in the 21st Century: From Industrialization to Sustainability (i ed.). San Diego, CA: Cognella. p. 36. ISBN978-1-609279-83-7.

- ^ Lisa Feldstein (2010). Malo André Hutson (ed.). Urban Communities in the 21st Century: From Industrialization to Sustainability (i ed.). San Diego, CA: Cognella. p. 526. ISBN978-1-609279-83-7.

- ^ Sevilla, Charles Martin (1971). "Asphalt Through the Model City: A Study of Highways and the Urban Poor". Journal of Urban Law. 49 (297): 298. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T. (1985). Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the U.s.a. . Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. p. 214. ISBN978-0-19-503610-seven.

- ^ Robert Fishman (2005). "Global Processes of Shrinkage". In Philipp Oswalt (ed.). Shrinking Cities Book i: International Inquiry (1 ed.). Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag. p. 71. ISBN978-3-7757-1682-6.

- ^ Ivonne Audirac (May 2009). Pallagst, Karina (ed.). "The Future of Shrinking Cities: Problems, Patterns, and Strategies of Urban Transformation in a Global Context" (.pdf). Institute of Urban and Regional Evolution Berkeley. IURD Monograph Series: 69. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Beverly H. Wright; Robert D. Bullard (2007). "Missing New Orleans: Lessons from the CDC Sector on Vacancy, Abandonment, and Reconstructing the Crescent Metropolis". The Black Metropolis In The Twenty-First Century: Race, Power, and Politics of Place (1 ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 175–176. ISBN978-0-7425-4329-4.

- ^ Jeffrey S. Lowe; Lisa K. Bates (17 October 2012). "Missing New Orleans: Lessons from the CDC Sector on Vacancy, Abandonment, and Reconstructing the Crescent Metropolis". In Margaret Dewar; June Manning Thomas (eds.). The City After Abandonment (one ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 151. ISBN978-0-8122-4446-5.

- ^ C. Ray Nagin (July ten, 2007). "Senate Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Disaster Recovery of the Us Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs". p. 2. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Renia Ehrenfeucht; Marla Nelson (2013). "Recovery in a Shrinking City: Challenges to Rightsizing Mail-Katrina New Orleans". In Margaret Dewar; June Manning Thomas (eds.). The City Subsequently Abandonment (i ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 142–147. ISBN978-0-8122-4446-5.

- ^ a b c Ehrenfeucht, Renia; Marla Nelson (11 May 2011). "Planning, Population Loss and Equity in New Orleans later Hurricane Katrina". Planning Practise & Research. 26 (ii): 134–136. doi:ten.1080/02697459.2011.560457. S2CID 153893210.

- ^ Nelson, Marla; Renia Ehrenfeucht; Shirley Laska (2007). "Planning, Plans, and People: Professional Expertise, Local Knowledge, and Governmental Activeness in Post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans". Cityscape: A Periodical of Policy Development and Research. 9 (3): 136. SSRN 1090161.

- ^ Willard-Lewis, Cynthia (April 5, 2007). "NO. 22605 MAYOR Quango Series" (PDF). Archived from the original (.pdf) on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Thomas, June Manning (2013). Redevelopment and Race: Planning A Effectively City in Postwar Detroit. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University. p. 83. ISBN978-0-8143-3907-7.

- ^ Gallagher, John (2013). Revolution Detroit: Strategies for Urban Reinvention. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne Land University. p. fifteen. ISBN978-0-8143-3871-1.

- ^ Andrew Herscher (2013). "Detroit Fine art City: Urban Decline, Aesthetic Product, Public Interest". The Metropolis After Abandonment (1 ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing. p. 69. ISBN978-0-8122-4446-5.

- ^ "Detroit Residential Parcel Survey: Citywide Report for Vacant, Open and Unsafe and Fire" (.pdf). Data Driven Detroit. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 21 Apr 2014.

- ^ a b Grey, Steven (2010). "Staying Put in Downsizing Detroit". Time Mag . Retrieved xix April 2014.

- ^ Christine Macdonland; Darren A. Nichols (9 March 2010). "Detroit's desolate center makes downsizing tough: Data shows viable neighborhoods are closer to suburbs". The Detroit News . Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ a b Ewing, Heidi and Rachel Grady (Directors) (2012). Detropia (motion picture show). United States: ITVS.

- ^ a b McGreal, Chris (17 Dec 2010). "Detroit mayor plans to shrink city past cut services to some areas: Services such every bit sewage and policing may be cut off to force people out of desolate areas where houses cost as little as £100". The Guardian . Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Sands, David (16 July 2012). "Detroit Bus Cuts Reveal Depths Of National Public Transit Crisis". Huffington Postal service . Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ a b Dolan, Matthew (xviii March 2014). "Detroit'due south Broken Buses Vex a Broke City: Bankruptcy Ways Common cold Waits, Hot Tempers for Residents in Need of a Ride". The Wall Street Journal . Retrieved 24 Apr 2014.

- ^ Stoll, Michael (February 2005). "Job Sprawl and the Spatial Mismatch between Blacks and Jobs". The Brookings Establishment – Survey Series: ane–8.

- ^ Grengs, Joe (2010). "Task accessibility and the modal mismatch in Detroit". Journal of Ship Geography. ten: 42–54. doi:x.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.01.012. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

External links [edit]

- Shrinking Cities. Research and Exhibition Project

- SCiRN™ (The Shrinking Cities International Research Network)

- Interview with German language expert Wolfgang Kil on Shrinking Cities in Federal republic of germany

- Professor Hollander's enquiry on shrinking cities

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shrinking_city

0 Response to "Cities Were Shrinking but Now Growing Again"

Post a Comment